Pterodactyls Over Brooklyn

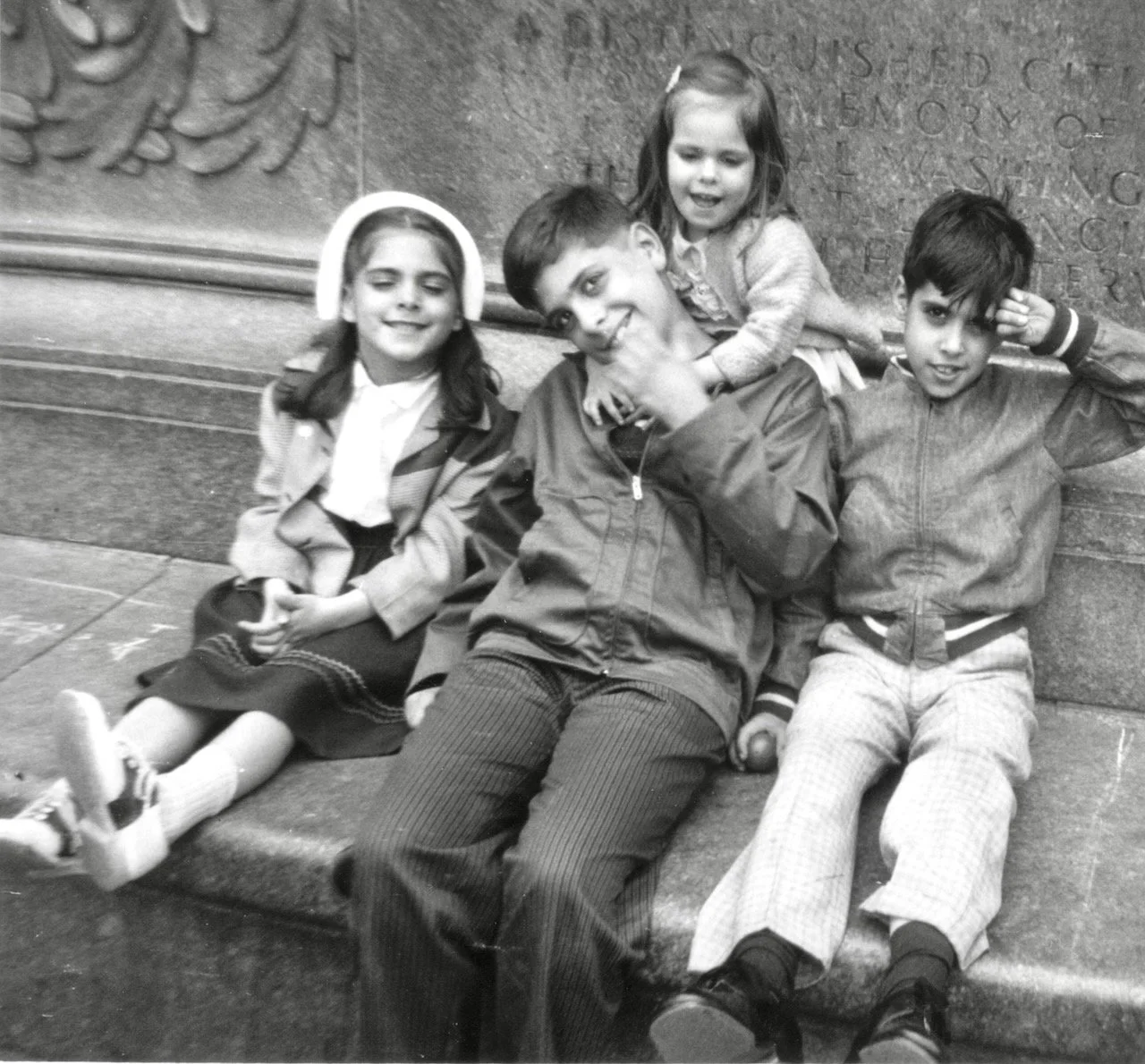

The photograph above shows the first four Carbone siblings in Prospect Park in the 1950s: me, Ralph, Marlene, and on the far right, my brother Eddie. Eddie’s birthday is this month—he would have been 78 years old—and he lives inside my heart always, but I’ve been thinking about him more than usual lately, for many reasons. I wrote this post about him years ago, and I want to share it here again as a way of honoring his memory. I wish you could have known him.

We raise our hands in horror as the triceratops approaches, trying desperately to flee but stumbling in its path. Meanwhile, a pterodactyl hovers ominously above the fire escapes and rooftops, its wings forming a skeletal arc against a plain gray sky -- it is a pursuit that never ends, a prolonged limbo, an always pending tale.

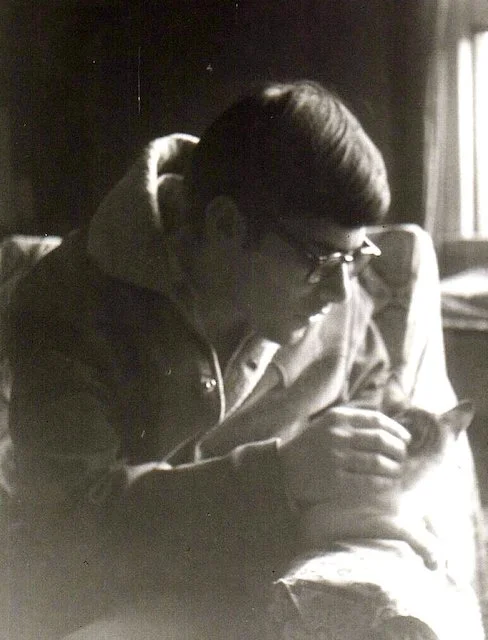

My brother Eddie took those snapshots in 1960 when he was thirteen years old and roaming the streets of Brooklyn with a plastic Brownie camera. Although I was one of his most frequent models, I had long forgotten about the photo shoots and was fascinated when I discovered the snapshots in a small cardboard box on its way to oblivion. I always wished I had more pictures of Eddie – over the years his image has fractured into its component elements: a pair of black-rimmed glasses, a cap of thick brown hair, a certain kind of smile that happened quickly and left you wondering why it seemed so sad. But the face as a whole is never in focus. My lens is blurred by time and loss.

So I was disappointed when I looked through this curious cache of photos, hoping for a new glimpse of the dearly loved companion of my childhood and finding instead brick walls and empty lots, the open pages of a monster magazine, the blankness of his own outstretched hand. I saw the familiar buildings of Coney Island Avenue, the gas station whose red Pegasus was the view from our front window, a stack of abandoned pots on a fire escape, and a clothesline whose mundane laundry that morning achieved a kind of immortality. I recognized the white steps of the boathouse by the lake at Prospect Park where we sat one summer day and sipped vanilla egg creams.

And then there were those dinosaur encounters, a series Eddie created by holding toy figures close to the camera and directing my oldest brother Ralph and me to pose in the distance. We were only too happy to oblige: our displays of terror are truly impressive, if a bit over the top. I guess you could say my brother invented special effects photography.

Although only three years older than me, Eddie was a magician and mentor, and I spent many hours under his spell. Armed with a toy gun and sometimes wearing the Davy Crockett hat that we jointly owned and cherished, Eddie scripted battles with imaginary Nazis, produced ingenious shadow shows cast upon a square of light on the wall, and transformed himself for my amusement into a repertoire of eccentric characters, each with his own funny voice and mannerisms. He was a talented artist who sketched intricate drawings in pencil and ink, created abstract melted crayon art (he called it radiator painting), and taught my best friend how to draw a nose -- "And not just in profile," she told me many years later, "but front on, the hard way!"

He taught me the names of all the dinosaurs and famous cinema monsters, how to fling clods of earth explosively into the street ("dirt bombs") and how to ride the red two-wheeler he had found by someone’s garbage can, rusty but salvageable. Most miraculously, he taught me how to read – with his help, random marks began to organize themselves into meaningful shapes, and my world suddenly opened.

Eddie loved to make my sister Marlene and me laugh. Sometimes he transformed himself into a character he called The Old Lady: he placed a white towel like a shawl upon his head and chided us in a tiny quivering voice. If we were sitting in the car watching people walk by, he talked for them as though they were puppets, giving them comical accents and personalities, concocting absurd little worries about which they would mutter and fret as they passed. I confess he sometimes created weather for pedestrians as well, with me as his gleeful accomplice, sprinkling water on befuddled passers-by from the window of our first-floor apartment.

I did not fully understand that Eddie was born with polycystic kidney disease, or all the ramifications of that fate. (I am humbled by how many things I didn't understand.) He was a sensitive boy, but he hid his tears, and he may have appeared odd to the outside world, but to me he was an ally and protector.

Eddie moved out of our turbulent household when he was still in his teens and tried a sort of grown up life in the city, off kilter and mostly solo, living in furnished rooms, working odd jobs, getting through college. Now and then he simply boarded a bus for distant and random destinations, hoping to solidify a plan along the way.

He was living in Atlanta and all set to start law school when his kidneys failed. A life on dialysis, far from home, would be difficult for anyone, but for Eddie, the world abruptly grew more frightening and obscure. At one point, in the midst of a crisis for which I was breathtakingly unprepared and ill-suited, I faced the responsibility of facilitating his admission to a psychiatric facility. I will never forget his look of betrayal and confusion when I left him there.

But my brother was brave. For years he drifted through various circumstances, intermittently hospitalized, trying to make sense of things, trying to live a life that mattered. He became an advocate for patients’ rights, writing letters and circulating petitions that only alienated those upon whom his care depended. He married someone wrong for him and it ended very badly. He was lonely and luckless but he never grew hard-hearted.

At the core of him always was the boy he was before he was so battered by the randomness of things. He loved five and dime stores and second-hand shops, stamps and coins and comics...and Mallowmars...remember those? He bought interesting old books and plastic toys, crammed them into manila envelopes, and shipped them to my toddler daughter, the niece he never met. He sent a paper lantern from Chinatown, wedding cake figurines, a small bag of miniature dinosaurs.

The last time I saw Eddie he was sitting in a slant of sunlight on the edge of a bed in San Francisco. His lips were cracked and chalky, and his whispered words circled us like aimless birds, disjointed and defeated. He was paranoid about his caregivers and certain that dialysis had become a plot to gradually kill him. I offered up my useless talk, toiletries, and pocket cash. I combed his matted hair and convinced myself that a walk outside would do him good. I held his arm, and with slow and painful steps we walked to the corner and back again. (Oh, what a monumental courage it can be just to wake up and get dressed!)

A few years later, he was back in New York. He had to have an operation for a defective heart valve, but he was debilitated already, and pneumonia set in. I have a letter he wrote me from his hospital bed. It hurts to read it, but I know what it says. He could see the lights of Manhattan from his window. He wanted to live. He promised he would approach everything differently if given the chance.

And so I hoped to find another image of my brother when I came upon that little box of photos, but there are no more pictures of him. I stared instead at inanimate objects -- solid, cryptic, and benign. Is it better to see what he saw than see him? His snapshots reveal a world one could invent and orchestrate. Fate could be kept at bay, pursuits were playful shams, and imagination ruled. My brother was creative and brilliant and funny and kind, but there was no place for him in what was real.

––––––––––

The decades pass. I am forever trying to make sense of things, as Eddie so long ago tried, and to live a life that matters. I became a teacher after he died, more for him than anyone. I thought it was a good way to keep his memory alive.

I learned early that fate is inequitable and unfair, and I have been granted a lucky life, and if so blessed, my goal is not to squander it.

I learned too that some people do not let hardship make them mean. Some people, even in the midst of struggle, draw upon a wellspring of kindness and imagination. And the most generous among us are often those who were given the least.

You know what else? I was chased by dinosaurs in Brooklyn, New York. I sat on the boathouse steps with my brother once, sipping a vanilla egg cream, and everything else was irrelevant.

I can never shed the sadness I feel about my brother’s life, but he also left some kind of laughter in me that never went away.

Edward Joseph Carbone (November 22, 1947 - May 10, 1992)