The Six of Us

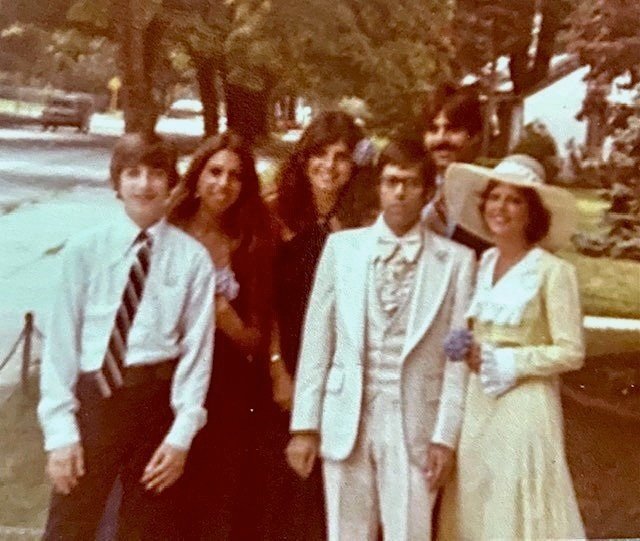

The photo above is of my siblings and me, taken on a gray Long Island day in the late 1970s. There were six of us, and this picture, which recently resurfaced, is the only one in existence of all of us together, the whole motley brood. From left to right, there’s Eric, Libbie, me, Eddie (foreground in the white suit), Ralph, and Marlene (in the hat and yellow dress). Eric, the youngest, was born twenty-one years after our oldest brother, Ralph. (I’m sixteen years older than Eric, and I still think of him as my “little” brother.) It’s hard to describe how much sadness and sweetness this photo evokes, how much loss and love.

The age gaps may help to explain how rare it was for us to be in one place at the same time. Some of us were far away–married, in school, or otherwise attempting life as adults––while others still lived at home. Unfortunately, “home” was a tumultuous setting, fraught with conflict, struggle, and illness. Those who could leave left promptly. I theorized that just as people flee when a bomb goes off, we had fled what felt like a domestic war zone, scattering early on, our own little diaspora. Even decades later, when I was lamenting the infrequency of get-togethers among the remaining siblings, other than for funerals and calamities, Eric wryly observed that survivors of the Titanic probably didn’t get together much to reminisce. It made sense. We associated one another with pain. We could mask it sometimes with a characteristic dark humor, but it also bled out into anguish at times, and terrible fights.

But here we are in this snapshot, together, all six of us.

I remember the day. Our father had died just a year or two earlier, and we were still reeling with that loss, but we were trying so hard to be okay. Eddie even dared to have a wedding, and this was at the reception. It was a misguided and short-lived marriage, and even on the wedding day, it was clearly doomed to fail. But Eddie had more than his fair share of problems, including the congenital kidney disease with which both he and Marlene were afflicted, and this was a touching stab at normalcy and a hopeful antidote to loneliness. You know what else? I honestly believe he wanted to offer up a happy event for a change. My wedding–he spoke the words proudly. Welcome to my wedding.

And this is what normal families do, we thought. They dress up and gather and celebrate weddings. We ignored the conspicuous lack of affection between the newlyweds, and the disdain with which the bride’s family seemed to view her chosen husband. When they clinked their glasses and called for a performative wedding kiss, Eddie refused to indulge them. The real implications of this whole spectacle were beginning to dawn on him, and he seemed oddly lost and estranged. But we six siblings drew closer together, discovering a genuine bond. Through our shared sorrow, our shared sense of humor, and some fundamental familial cognizance, we experienced a profound connection that we hadn’t even realized was intact. We seemed to have a language all our own.

Yes, I was part of a litter once. And so much of how I learned to relate to other humans was taught to me by my early interactions with my siblings. I thought in the plural as much as the singular. I knew what it was like to be teased and tormented by older brothers, but how protective they could be at the sign of a threat from outside. I knew what it was like to huddle together in fear or sadness, to be called upon for rescue, or to laugh til we peed our pants. We scripted stories and games, vigorously participated in operatic family fights, and gave each other counsel. There were rifts and alliances, painful misunderstandings, and a pervasive sense of worry, but though we broke apart and went our separate ways, there was in the beginning a foundational kind of “we” about us.

Within a month or two after the wedding, Eddie’s wife left him. While he was on dialysis, her brothers emptied the apartment of everything of value. They even absconded with the little tabletop radio that had been his connection to some soothing and staticky elsewhere––fragments of music, vague voices as though underwater, a gentle current of company, suddenly gone; the theft of this particular object was purely spiteful. Meanwhile, illness took its relentless toll, and things kept getting worse. Eddie died at the age of forty-five. Less than a decade later, after several kidney transplants and years on dialysis, our sister Marlene died, also at the age of forty-five.

Maybe it’s the singularity of this long-lost photograph that renders it so precious, the fact of its being the only one of its kind. No other evidence exists to show that we were ever all together. There were no orchestrated photo shoots for this gang, no affable uncles at holiday feasts with cameras at the ready. There is nothing but this blurry Kodak print, probably developed at a corner drugstore, shared and stashed, rediscovered nearly half a century later.

I look at it now and the moment comes into focus, shimmering. It rained a little that day. I can almost smell the wet grass and puddled pavement. I can see the silvery gray of that flat East coast sky, the leafy trees, the pink clusters of azalea. I watched as Eric put up a big green and white striped umbrella, and I remember the surprising burst of it opening, the bloom of color, the beads of rain. He was just a gangly boy in a white shirt holding an umbrella, bemused and brave. I felt a great surge of tenderness for him––and for all of them. These were my people. Our hearts were battered, but here we were, all six of us together, trying to be happy, trying to find our footing, one of us so plucky as to have an actual wedding. That kind of spirit counts for something.

I’m learning a lot lately about the gifts I received from the members of my original family. Sometimes the gifts shine so brightly, they override the sorrow of the tragedy and loss. There were six of us once, and here we are, assembled in our finery. We were a ship without a rudder, a frigate already beginning to splinter and drift, embarking on a vast sea to varied destinies. What if we had held one another more tightly? I’ll never know.

I see them in my dreams, but they’re always out of reach.